independent

media

People-powered media that allows you to tell your own story through media. Videos reach a larger local audience through our community distribution platforms.

media arts

PROGRAMS

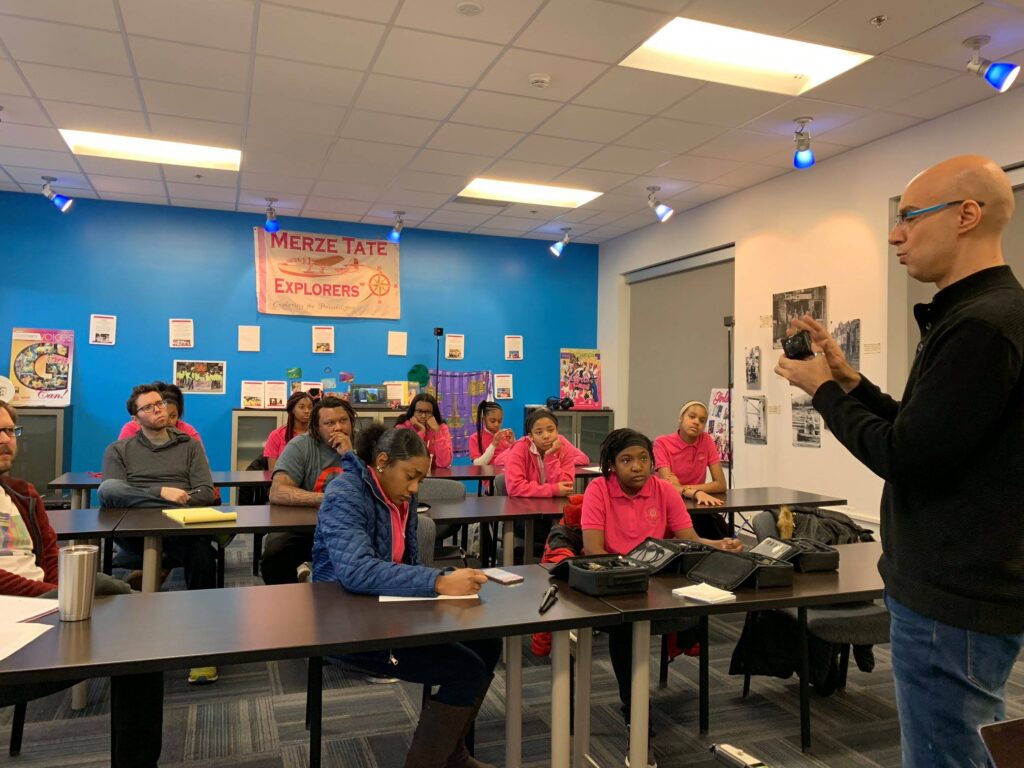

Our programs provide hands-on opportunities to learn digital media and television from concept to distribution to produce local media with a clear civic purpose.

Content

studio

Partner with our team of industry professionals and apprentices to produce local television and expand your audience.

civic

info

A local storytelling platform amplifying community news so you can be informed and engaged.

PMN Storyboard

Stronger Journalism for Stronger Communities

SW Michigan Journalism Collaborative given grant to cover youth mental health

Youth Media Summer Camps 2024!

Youth Media Summer Camps 2024 at Public Media Network!

Tell Community Stories with Amplify Kalamazoo

Join Amplify Kalamazoo and Share Community Stories! Want to see more…

sign up for our newsletter

PMN Connector

Thanks to our funders & sponsors

Access to media production resources and local information is made possible by the support of people like you.

Donate today and add your name to our list of supporters.